TikTok Never Wanted To Be Political. Too Late. Tiktok Memes

As 24 million acres of Australia burned in record bushfires between September and January, Australian teens turned to TikTok. Chloé Hayden, a 22-year-old motivational speaker and YouTuber based in Victoria, had barely used the video-sharing app, but her peers were flooding it with their and footage of the dense smoke as a way of raising awareness among a largely ignorant public.

was a perfect encapsulation of the TikTok sensibility: She used a popular meme format to show the hypocrisy of the lack of media attention by comparing it to the immediate outpouring of financial support after the Notre Dame fire. It was equal parts funny and incisive, and ended up being viewed nearly 300,000 times.

“I love that through the use of short comedy sketches, teens are getting a bigger point across than most lengthy, informative articles posted by some old bloke who we can’t relate to in the slightest,” she explains. “It’s both parts a coping mechanism and an incredible way to speak our minds where we’re all equal, and I genuinely don’t think there’s any other platform that you can do that in a similar way.”

TikTok has, in its barely year and a half of existing, become the most effective way for a random person to spread a message to the widest possible audience in the shortest amount of time. It takes the best of Twitter (brevity, as videos can be a maximum of 60 seconds but most are much shorter) and YouTube (the ability to see someone’s face as they’re speaking to you) and adds the ability to go viral with virtually zero followers.

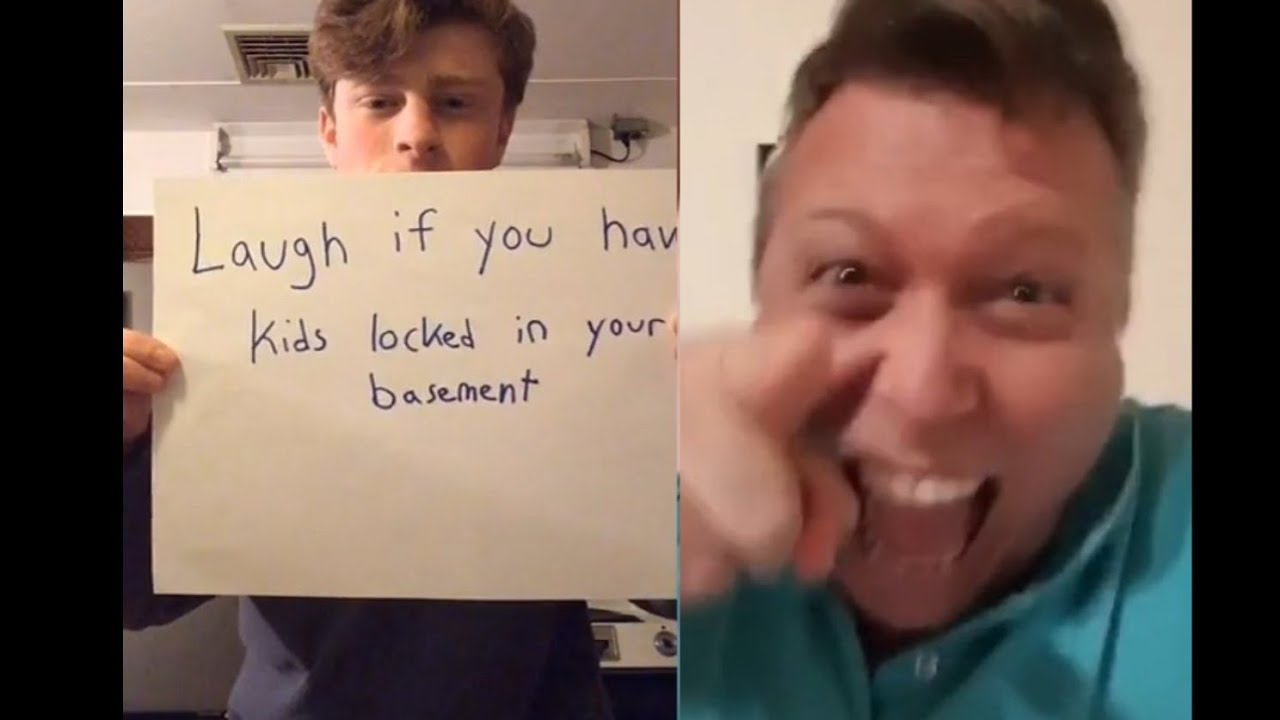

That the app is populated largely by teens also means that so much of what happens on it participates in a brand of ironic internet comedy that complicates the idea of serious news-sharing. TikTok videos on geopolitical events, from the Australian fires to the vague threat of World War III, can be viewed variously as awareness-spreading of underreported stories, coping mechanisms, exercises in nihilism, or goofy videos that no one should spend too much time analyzing.

Though it’s always tried to position itself as a joyful space for creating and viewing silly and inspiring content, TikTok has unintentionally become one of the best means of disseminating ideas on the internet. It’s a power that’s being used for better or for worse, and largely by minors.

TikTok was never supposed to be political. The app was expressly designed to discourage news-sharing — its home feed is non-chronological, and there are no visible timestamps for when a video is posted, making it nearly impossible to understand what happened when. Political advertisements are not allowed, and until recently, TikTok had vague content guidelines that reportedly encouraged moderators to . Its slogan is “Make your day,” presumably by distracting you from *gestures widely at everything*.

TikTok was never supposed to be political, but of course it was always going to be. During 2019’s widespread climate strikes, TikTokers used jokes about e-girls to spread awareness about e-missions. When Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was revealed to have worn brownface, TikTok had fun brutally roasting him. In November, a New Jersey teen posted a are, too.

Most importantly, millions of regular people are on TikTok, all of whom have at least some awareness of what happens in the world and who probably have opinions about it. In the first week of 2020, just a few days after memes about “new year new me” and leaving negativity in 2019 proliferated on the internet, the world seemed to explode: President Trump ordered the assassination of Quassem Soleimani, .

World War III seemed imminent, but on TikTok it was already raging. wrote one TikToker while doing a Fortnite dance.

“I just thought the idea of bringing my entire skin care routine with me to the battlefield would be a little extra and would earn a few laughs,” Tuazon tells me about his K-beauty WW3 TikTok. He likes the app because it gives him a chance to see average kids, no matter their country of origin, ethnicity, or sexual orientation, having fun and laughing together.

It’s the same for Juana Isabelle Sarenas, an 18-year-old student in Hong Kong who recently posted a video about “Cabin 6,” “the theoretical cabin where all the cool TikTok kids will end up when Trump is impeached and President Mike Pence sends queer teens to conversion-therapy summer camp.”

“The LGBT community there is huge,” Sarenas says of TikTok. The jokes “don’t erase the tragic events — if anything, they use the memes to bring light to them in a humorous way. I learned more about concentration camps and other horrifying current events from TikTok than I had any other platform.”

Cabin 6 memes, in general, are a pretty joyous way to react to the reality that the US vice president . “I just find it funny to joke about that — like summer camp with the fellow gays.”

Like the rest of the internet, as much as TikTok is a place for blasé nihilism — kids using the same meme format as Chloé’s.

Nwanne was used to the kind of discourse that takes place in activist and academic circles on Twitter and Instagram, with long threads and jargon-y paragraphs. “It’s a little difficult to engage on Twitter because if you ask the wrong question to the wrong person ... there will be a pile-on. You’ll get kicked the shit kicked out of you,” Nwanne says with a laugh. “But with a platform like TikTok, it’s way more accessible. I’m dancing. It’s a joke. It’s a lot easier to teach or to spread an idea when people are laughing.”

The subway fare video helped Nwanne gain 10,000 followers in a month on TikTok, where they continue to post videos about race, queer identity, capitalism, and leftist politics. “I think TikTok as a tool for education can be so revolutionary, and I would really love to see more people on my side of the political spectrum using it, moving away from these academic Twitter threads. Let’s meet the people where they are.”

It’s much easier to see the humanity of someone whose ideas you’re hearing when you can actually see them. The dominant TikTok aesthetic is a person in their own home, alone, speaking to the camera without knowing who will end up seeing their face on their screen. It’s like YouTube — one of the most effective platforms for sharing ideas, for better or for worse — but TikToks take even less effort to produce.

“Conversations are difficult to have on Twitter or Instagram because of how reactive everybody is on those apps,” Nwanne says. “Comments on a video about the Australian fires were like, folks asking questions and people answering them. On Twitter or Instagram they’d be like, ‘How dare you ask the question?’ The community’s a lot chiller, and I do think it’s because they’re younger, and so they don’t know to be pretentious douchebags yet.”

“I always compare TikTok to all of the rhymes and hand games that we played in middle school,” says Sophie Dickinson, an associate editor at Know Your Meme who covers TikTok. “The bushfires, other things that are happening now, it’s all the same jokes over and over and over again. It has to do with whatever the popular opinion is. It could be dangerous, but it’s also nice for kids to be coming together over something that might be very difficult and challenging to wrap their heads around.”

It would be easy to make TikTok out to be a utopian Gen Z playground, where authenticity sells and love wins and the rest is mostly just dancing, but that’s not the whole story. Nwanne, for instance, doesn’t read their comments because they say the platform is often quite conservative — “like Facebook-lite.” The #impeachment hashtag on TikTok seems to have nearly as many earnest Trump supporters as it does people poking fun at the president .

TikTok has some of the same political pitfalls as YouTube — to briefly panic over the idea of being forced to join the Army, even though the US hasn’t had a draft since 1973.

Bad stuff has been happening in the world forever, and the internet has always been full of very funny and very sad people to make jokes out of it. TikTok is now a crucial part of that machine, one that can set the discourse in practically zero time. Whatever comes of it, Nwanne knows one thing is certain: “We’re gonna set some shit on fire on TikTok.”

Twice a week, we’ll send you the best Goods stories exploring what we buy, why we buy it, and why it matters.

0 Comments

Post a Comment